Murder By Any Other Name

by Scott Ritter, published on Consortium News, November 6, 2021

On Aug. 29, the United States murdered ten Afghan civilians in a drone strike. The U.S. Air Force Inspector Gen., Lt. Gen. Sami D. Said, was appointed on Sept. 21, to lead an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the attack. On Nov. 3, Gen. Said released the unclassified findings of his investigation, declaring that while the incident was “regrettable,” no crimes were committed by the U.S. forces involved.

The reality, however, is that the U.S. military engaged in an act of premeditated murder violative of U.S. laws and policies, as well as international law. Everyone involved, from the president on down committed a war crime.

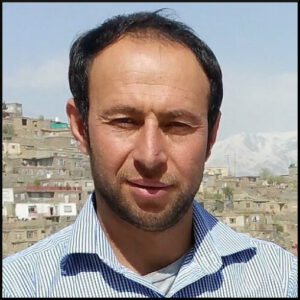

Their indictment is spelled out in the details of what occurred before and during the approximately eight hours a U.S. MQ-9 “Reaper” drone tracked Zemari Ahmadi, an employee of Nutrition and Education International, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization that has been operating in Afghanistan since 2003, working to fight malnutrition among women and children who live in high-mortality areas in Afghanistan.

During those eight hours, the U.S. watched Ahmadi carry out mundane tasks associated with life in war-torn Kabul circa Aug. 2021. The U.S. watched until the final minutes leading up to the decision to fire the hellfire missile that would take Ahmadi’s life, and that of nine of his relatives, including seven children.

“The investigation,” Gen. Said concluded in his report, “found no violation of law, including the Law of War.” One of the unanswered questions relating to this conclusion was the precise nature of the framework of legal authorities at play at the time of the drone strike, in particular the rules and regulations being followed by the U.S. military regarding drone strikes, and issues pertaining to Afghan sovereignty when it came to the use of deadly force by the U.S. military on Afghan soil.

At the time of the drone strike that murdered Zemari Ahmadi and his family, the policies governing the use of armed drones was in a state of extreme flux. In an effort to gain control over a program which, by any account, had gotten out of control in terms of killing innocent civilians, then-President Barack Obama, in May 2013, promulgated a classified Presidential Policy Guidance (P.P.G.) document entitled “Procedures for Approving Direct Action Against Terrorist Targets Located Outside the United States and Areas of Active Hostilities.”

The 2013 P.P.G. directed that, when it came to the use of lethal action (a term which incorporated direct action missions by U.S. Special Operation forces as well as drone strikes), U.S. government departments and agencies “must employ all reasonably available resources to ascertain the identity of the target so that the action can be taken.” The document also made clear that “international legal principles, including respect for sovereignty and the law of armed conflict, impose important constraints on the ability of the United States to act unilaterally—and the way in which the United States can use force.”

The standards for the use of lethal force set forth in the 2013 P.P.G. contain two important preconditions. First, “there must be a legal basis for using lethal force.” A key aspect of this legal basis is a requirement that the U.S. have the support of a host government prior to the initiation of any lethal force on the territory of that nation. This support is essential, as it directly relates to the issue of sovereignty commitments under the U.N. Charter.

When the 2013 P.P.G. was published, the U.S. had the express permission of the Afghan government to carry out lethal drone strikes on its territory for the purposes of targeting both the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Later, this authorization would extend to encompass the Islamic State-Khorasan Province, or ISIS-K.

In 2017, then-President Donald Trump issued new guidance which loosened the conditions under which lethal force could be used in Afghanistan, including the use of armed drones. The Afghan government continued to provide host nation authorization for these strikes. When President Biden assumed office, in January, he immediately directed his National Security Council to begin a review of the policies and procedures surrounding the use of armed drones in Afghanistan.

One of the issues addressed in this review was whether the Biden administration would return to the Obama-era rules requiring “near certainty” that no women or children are present in an area targeted for drone attack or retain the Trump-era standard of only ascertaining to a “reasonable certainty” that no civilian adult men were likely to be killed.

Complicating matters was the fact that the Biden administration was preparing for the complete withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan, which required that the rules and procedures for use of armed drones in Afghanistan be altered to reflect a new reality where U.S. forces were no longer being directly supported, and that the armed drone program would be conducted in an environment where the Afghan government was the exclusive recipient of armed drone support. These new rules and procedures were part of what the Biden administration called its “over the horizon” (OTH) counterterrorism strategy.

Before the new OTH policies and procedures directive could be issued, however, the reality on the ground in Afghanistan changed completely, making the policy document obsolete before it was even issued. The rapid advance of the Taliban, coupled with the complete collapse of the Afghan government, threw into question the legal underpinnings regarding the authority of the U.S. government to conduct armed drone operations in Afghanistan.

The new rulers of Afghanistan, the Taliban, did not approve of U.S. armed drone operations. Instead, the Taliban had executed a secret annex to the February 2020 peace agreement reached with the Trump administration regarding its commitment to dealing with counterterrorism issues in Afghanistan once the U.S. withdrew. President Biden determined that his administration would be bound by the terms of that agreement.

Two points emerge from this new environment—first, from a legal standpoint, the U.S. military remained bound by the “reasonable certainty” of the Trump-era policies regarding the use of armed drones, and second, from the standpoint of international law as it relates to sovereignty commitments, the U.S. had no legal authority to conduct armed drone operations over Afghanistan.

While the U.S. had not formally recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, President Biden’s commitment to adhere to commitments made under the terms of the February 2020 peace agreement, coupled with the fact that the U.S. was engaged in active negotiations with the Taliban in Doha and in Kabul regarding issues pertaining to security of U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan and Kabul, make clear that for all sense and purpose, the U.S. treated the Taliban as if they were the sovereign authority in Afghanistan.

In Order to Be Legal

For U.S. drone operations on Aug. 29, to be legal in Afghanistan, the U.S. government had to either gain public approval for these operations from a sovereign authority, gain private approval from a sovereign authority, or else demonstrate that a sovereign authority was unable or unwilling to act, in which case the U.S. could, under certain conditions, consider unilateral action.

Gen. Said does not provide any information as to how he ascertained U.S. compliance under international law. Public statements by the Taliban appear to show that they did not approve of U.S. drone strikes on the territory of Afghanistan. Indeed, when the U.S. carried out a similar drone attack, on Aug. 27, targeting what it claimed were ISIS-K terrorists, the Taliban condemned the strike as a “clear attack on Afghan territory.”

The second precondition set forth in the 2013 P.P.G. authorizing the use of lethal action was that the target must pose “a continuing, imminent threat to U.S. persons.” In his presentation on the Aug. 29, drone strike, Gen. Said stated that “[i]ndividuals directly involved in the strike…believed at the time that they were targeting an imminent threat. The intended target of the strike, the vehicle, its contents and occupant, were genuinely assessed at the time as an imminent threat to U.S. forces.”

When promulgating its 2013 P.P.G. on drone strikes, the Obama administration adopted an expanded definition of what constituted an “imminent threat” published by the Department of Justice in 2011, which eschewed the notion that in order to be considered “imminent”, a threat had to be a specific, concrete threat whose existence must first be corroborated with clear evidence.

Instead, the Obama administration adopted a new definition that held that an imminent threat was inherently continuous because terrorists are assumed to be continuously planning attacks against the U.S.; all terrorist threats are considered both “imminent” and “continuing” by their very nature, removing the need for the military to gather information showing precisely when and where a terrorist threat was going to emerge.

To make the case of an “imminent” (and, by definition, “continuing”) threat, all the U.S. needed to do in the case of Zemari Ahmadi was create a plausible link between him and potential terrorist activity. According to Gen. Said, “highly classified” (i.e., Top Secret) intelligence was interpreted by U.S. personnel to ascertain the existence of a terrorist threat.

This assessment was used to create a linkage with Ahmadi, and the subsequent “observed movement of the vehicle and occupants over an 8-hour period” resulted in confirmation bias linking Ahmadi to the assessed terrorist threat.

Who Was in Command?

Zemari Ahmadi’s actions on Aug. 29, did not trigger the drone attack. Instead, the U.S. appeared to be surveilling a specific location in Kabul, looking for a White Toyota Corolla (ironically, the most prevalent model and color of automobile operating in Kabul) that was being converted by ISIS-K terrorists into a weapon to be used against U.S. forces deployed in the vicinity of Kabul International Airport.

This safe house was located about five kilometers west of Kabul International Airport, in one of Kabul’s dense residential neighborhoods. The specific source of this information is not known but given Gen. Said’s description of it as “highly classified”, it can be assumed that this information involved the interception of specific communications on the part of persons assessed as being affiliated with ISIS-K, and that these communications had been geolocated to a specific area inside Kabul.

One of the issues confronting the U.S. during this time was the absolute chaotic nature of the command, control, communications, and intelligence (C3I) infrastructure that would normally be in place when carrying out any military operations overseas, including something as politically sensitive as a lethal drone strike. It wasn’t just the policy guidelines for the use of lethal drone strikes that were in limbo on Aug. 29, 2021, but also who, precisely, oversaw what was going on regarding the employment of drones in Afghanistan.

The U.S. military and C.I.A. had completely withdrawn from Afghanistan when the decision was made to begin noncombatant evacuation operations (N.E.O.) operating from Kabul International Airport. The deployment of some 6,000 U.S. military personnel was accompanied by an undisclosed number of C.I.A. and Special Operations forces who were tasked with sensitive human and technical intelligence collection, including intelligence sharing and coordination with the Taliban.

To support this activity, an expeditionary joint operations center (JOC) was established by U.S. forces, led by Rear Admiral Peter Vasely, a Navy SEAL originally dispatched to Afghanistan to lead Special Operations, but who took over command of all forces when the former commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, Gen. Scott Miller, left in July 2021.

Admiral Vasely was assisted by Major Gen. Chris Donahue, a former Delta Force officer who commanded the 82nd Airborne Division. While both Vasey and Donahue were experienced combat commanders, they were singularly focused on the issue of securing the airport and evacuating personnel under a very constrained timeline. Managing drone operations would be handled elsewhere.

As part of President Biden’s vision for Afghanistan post-U.S. evacuation (and pre-Afghan government collapse), the Department of Defense had established what was known as the Over the Horizon Counter-Terrorism Headquarters at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar. Commanded by Brigadier Gen. Julian C. Cheater, Over the Horizon Counter-Terrorism, comprised of 544 personnel, was tasked with planning and executing missions in support of Special Operations Command-Central across four geographically-separated locations in the United States Central Command area of responsibility, including Afghanistan.

But Gen. Cheater had only assumed command in July, and his organization was still getting settled into its new quarters (Brigadier Gen. Constantin E. Nicolet, the deputy commanding general for intelligence for the Over the Horizon Counter-Terrorism headquarters, did not arrive until Aug. 11.) As such, much of the responsibility for coordinating drone operations into the overall air campaign operating in support of the Kabul N.E.O. (which, in addition to multiple C-17 and C-130 airlift missions per day, included AC-130 gunships, B-52 bombers, F-15 fighters, and multiple MQ-9 Reaper drones) was handled by Central Command’s Combined Air Operations Center (C.A.O.C.), located at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar.

The Video Source

Gen. Said, in his presentation, made mention of “multiple video feeds” when speaking of the information being evaluated by U.S. military personnel regarding the strike that killed Ahmadi and his family. This could imply that more than one MQ-9 drone was operating over Kabul that day, or that video feeds from other unspecified sources were also being viewed.

It also could be that the MQ-9 that fired the Hellfire missile that killed Ahmadi and his nine relatives was flying by itself; the MQ-9 carries the Multi-Spectral Targeting System, which integrates an infrared sensor, color, monochrome daylight TV camera, shortwave infrared camera, the full-motion video from each which can be viewed as separate video streams or fused together. In this way, one drone can provide several distinct video “feeds”, each of which can be separately assessed for specific kinds of information.

The MQ-9 is also capable of carrying an advanced signals intelligence (SIGINT) pod, producing yet another stream of data that would need to be evaluated. It is not known if this pod was in operation over Kabul on Aug. 29. However, according to The New York Times, U.S. officials claim that that the U.S. intercepted communications between the white corolla and the suspected ISIS-K safehouse (in actuality, the N.I.E. country director’s home/N.I.E. headquarters) instructing the driver (Ahmadi) to make several stops.

Logic dictates that the U.S. military kept at least one, and possible more, MQ-9’s over Kabul at all times, providing continuous intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance overwatch during the conduct of the evacuation operation. The primary MQ-9 unit operating in the Persian Gulf region at the time was the 46th Expeditionary Attack Squadron, which operated out of Ali Al Salem Air Base, in Kuwait.

Given the logistical realities associated with drone operations over Afghanistan, which required a lengthy flight down the Persian Gulf, skirting Iran, and then over Pakistan, before reaching the central Afghanistan region, the 46th Expeditionary Attack Squadron more than likely forward deployed a ground control station used to take off and recover the MQ-9 drones, along with an undisclosed number of drone aircraft, to Al Udeid Air Base, in Qatar.

The time of flight from Al Udeid to Kabul for an MQ-9 drone is between 5 and 6 hours; a block 5 version of the MQ-9, such as those operated by the 46th Expeditionary Attack Squadron, can operate for up to 27 hours. It is possible that a single MQ-9 drone was on station for the entire period between when Ahmadi was first taken under surveillance until the decision to launch the Hellfire missile that killed him was made; it is also very possible that there was a turnover between one MQ-9 and another at some point during the mission. In either instance, a long-duration mission such as that being conducted on Aug. 29, would have been logistically and operationally challenging.

The crew from the 46th Expeditionary Attack Squadron was responsible for launching and recovering the MQ-9 drone from its operating base; once in the air, control of the drone was turned over to drone crews assigned to the 432nd Expeditionary Air Wing, based out of Creech Air Base, in Nevada. These crews work with the Persistent Attack and Reconnaissance Operations Center, or PAROC, also located at Creech Air Base.

The PAROC coordinates between the 432nd Wing Operations Center, which serves as the focal point for combat operations, and the Over the Horizon Counter-Terrorism Headquarters and Central Command Combined Air Operations Center, both out of Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. The PAROC serves as a singular focal point for mission directors, weather analysis, intelligence analysis and communications for drone operations over Afghanistan.

At each node in this complex command and control system, the video feeds from the drone(s) involved can be monitored and assessed by personnel. Such an overlapping network of agencies was implied by Gen. Said in his presentation, when he spoke of interviewing “29 individuals, including 22 directly involved in the strike” for his report.

Given that Gen. Said’s remit is limited to the military forces involved, it is not known if he interviewed another party reportedly involved in the drone strike—the C.I.A. Multiple sources have indicated that C.I.A. analysts were involved in evaluating the video feeds associated with the drone strike of Aug. 29, and that they provided input regarding the nature of the target.

C.I.A. Involvement

The C.I.A. operates what is known as the Counterterrorism Airborne Analysis Center out of its Headquarters in Langley, Virginia. There, a fusion cell of intelligence analysts drawn from across the U.S. intelligence community monitor a wall of flat screen monitors that beamed live, classified video feeds from drones operating from around the world, including Afghanistan.

The C.I.A.’s involvement suggests that because of the confusion surrounding the legality of drone operations in Afghanistan following the collapse of the Afghan government, the Biden administration opted to conduct drone operations under Title 50, covering covert C.I.A. activities, as opposed to Title 10, which cover operations conducted under traditional military chain of command.

In any event, what is known is that an MQ-9 drone, flown by pilots from the 432nd Expeditionary Wing operating out of Creech Air Base, in Nevada, was surveilling a specific neighborhood in Kabul on the morning of Aug. 29, where intelligence sources indicated an ISIS-K terrorist cell was in the process of converting a white Toyota Corolla into a weapon—perhaps a car bomb—that was to be used against U.S. forces operating at Kabul International Airport.

The U.S. forces operating in Afghanistan were on high alert—on Aug. 26, ISIS-K fighters had launched a coordinated attack using suicide bombers and gunmen on a U.S. checkpoint at the airport, killing 13 U.S. service members and some 170 Afghans, including nearly 30 Taliban fighters.

According to a timeline put together by The New York Times, Zemari Ahmadi left his home, located in a neighborhood about two kilometers west of the airport, in a white Toyota Corolla owned by his employer, Nutrition and Education International (N.E.I.). Ahmadi had worked with N.E.I. since 2006 as an electrical engineer and volunteer, helping distribute food to Afghans in need.

The country director for N.E.I. had called Ahmadi at around 8:45 am, asking him if he could stop by the country director’s home and pick up a laptop computer. Ahmadi left his home at around 9 am, and drove to the country director’s home, located about five kilometers northwest of the airport. The drone operators were surveilling the compound where the country director lived, having assessed that it was an ISIS-K safe house.

It is at this point the intelligence failures that led to the murder of Ahmadi and his family began. The country director, whose name has been omitted for security reasons, is a well-known individual whose biometric information, including place of work and residence, has been captured by a highly classified Department of Defense biometric system called the Automatic Biometric Identification System, or ABIS. ABIS, part of what the U.S. calls its strategy of “Identity Dominance”, was specifically set up to help identify targets for drone strikes and was said to contain more than 8.1 million records.

The ABIS, when integrated with other data bases such as the Afghanistan Financial Management Information System, which held extensive details on foreign contractors, and an Economy Ministry database that compiled all international development and aid agencies (such as N.E.I.) into a singular searchable Geographic Information System, or G.I.S., gives an analyst the ability to scroll a cursor over a map of Kabul, coming to rest over a given building, and immediately accessing information about who resides there.

Both the country director and Ahmadi, as Afghans affiliated with western aid organizations who moved with relative freedom around Kabul, were included in these data bases.

Massive Intelligence Failure

The fact that a U.S. intelligence analyst could confuse the known residence/headquarters of a U.S.-funded aid organization with an ISIS-K safe house is inexcusable, if indeed these data bases were available for query.

It is possible that (because of the transitional environment) the events of Aug. 29 transpired with no definitive rules of engagement in place, and that the command and control structure was in a high state of flux, so that the data base was either shut down or otherwise inaccessible. In any case, the inability to access data that had been collected over the course of many years by the United States for the express purpose of helping facilitate the counterterrorism-associated targeting of armed drones represents an intelligence failure of the highest order.

The community of analysts, spread across several time zones and distinct geographical regions, representing agencies with differing legal and operational frameworks, began monitoring the movement and activities of Ahmadi. He picked up a laptop computer from the country director, which was stored in a black carrying case of the kind typically used to carry laptop computers. Unfortunately for Ahmadi, the ISIS-K suicide bombers who attacked the U.S. position at Kabul International Airport on Aug. 26 carried bombs that had been placed in similar black carrying cases, reinforcing what Gen. Said called a chain of “confirmation bias.”

Ahmadi then went on a series of excursions, picking up coworkers at their homes, dropping them off at various locations, stopping for lunch, and distributing food. Near the end of the day, Ahmadi returned to the N.E.I. headquarters where he used a hose to fill up plastic containers with water to bring home (there was a water shortage throughout Kabul, and Ahmadi’s home had no running water.)

Analysts watching Ahmadi’s actions somehow mistook the act of using a garden hose to fill plastic jugs with water as him picking up plastic containers containing high explosives that could be used in a car bomb—another case of “confirmation bias.”

At least 22 sets of eyes were watching this, using multi-spectral cameras capable of ascertaining movement of water, temperature variations, all in high-resolution video feeds. How not a single pair of eyes picked up on what was really happening is, yet again, a huge failure of intelligence, either in terms of training as an imagery analyst, poor analytical skills, or both.

But even with all of this “confirmation bias” weighing in favor of classifying Ahmadi as an “imminent threat”, neither he nor his family were condemned to die. Under International Human Rights Law, lethal force is legal only if it is required to protect life (making lethal force proportionate) and there is no other means, such as capture, of preventing that threat to life (making lethal force necessary).

If Ahmadi’s car, upon leaving the country director’s home, had headed toward a U.S.-controlled checkpoint around Kabul International Airport, then U.S. personnel monitoring the drone feed would have had every right, under the procedures then in place, to consider Ahmadi a “continuing imminent threat” to American life, thereby freeing the drone crew to fire a Hellfire missile at the vehicle to destroy it.

Instead, he drove home, pulling into the interior courtyard of his building complex. At this juncture, Ahmadi and his vehicle could not, under any circumstance, be considered an active threat to American life. Moreover, with the vehicle immobile and still under observation, options could now be considered for “other means”, such as capture, to remove the vehicle and Ahmadi as a potential future threat.

While the U.S. and the Taliban had an implicit agreement that U.S. forces would not operate outside the security perimeter of Kabul International Airport, the Taliban were fully capable of sending a force to investigate and, if necessary, detain Ahmadi and his vehicle. The U.S. admits to actively sharing intelligence with the Taliban and acknowledge that the Taliban had proven itself capable of acting decisively to neutralize threats based upon the information provided by the U.S.

The Taiban interest in stopping a suicide bomber was manifest—they had suffered twice as many killed than the U.S. in the Aug. 26 attack on the Airport, and were sworn enemies of ISIS-K. All the U.S. had to do was pass the coordinates of Ahmadi’s home to the Taliban, and then sit back and watch as the Taliban responded. If the Taliban failed to act, or Ahmadi attempted to drive away from his home in the white corolla, then the U.S. would be within its rights under international law to attack the car using lethal force.

However, to get there the U.S. first needed to cross the legal hurdle of exhausting “other means” of neutralizing the potential threat posed by Ahmadi’s car. They did not, and in failing to do so, were in violation of international law when, instead, they opted to launch a Hellfire missile.

The decision to fire the Hellfire missile was made within two minutes of Ahmadi arriving at his home. According to The New York Times, when he arrived, his car was swarmed by children—his, and those of his brother, who lived with him. For some reason, the presence of children was not picked up by any of the U.S. military personnel monitoring the various video feeds tracking Ahmadi.

The drone crew determined that there was a “reasonable certainty”—the Trump-era standard, not the “near certain” standard that would have been in place had the Biden administration published its completed policy guidance document regarding drone strikes—that there were no civilians present. How such a conclusion can be reached when, on review, the video clearly showed the presence of children two minutes before the Hellfire missile was launched—has not been explained.

But Gen. Said wasn’t the only one who saw children on the video feed. At the C.I.A.’s Counterterrorism Airborne Analysis Center in Langley, at least one analyst working in the fusion cell there saw the children as well. According to media reports, the C.I.A. was only able to communicate this information to the drone operators who fired the Hellfire after the missile had been launched, part of the breakdown in communications that Gen. Said attributed to the chain of mistakes that led to the deaths of Ahmadi and his family.

What Gen. Said failed to discuss was the communications channels that the C.I.A. information had to travel to get to the drone operators. Did the C.I.A. have a direct line to the pilots of the 432nd Expeditionary Wing? Or did the C.I.A. need to go through the Over the Horizon Counter-Terrorism headquarters, the Central Command’s Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC), the Persistent Attack and Reconnaissance Operations Center, or PAROC, or the 432nd Wing Operations Center, which communicated directly with the drone crew?

According to The New York Times, the tactical commander made the decision to launch the Hellfire missile, another procedural holdover from the Trump-era, which did away with the need for high-level approval of the target before lethal force could be applied.

The professionalism of those involved in reviewing the drone feed was further called into question when the analysts, observing a post-strike explosion of a propane tank in the courtyard of Ahmadi’s apartment complex, mistook the visual signature produced as being that of a car bomb containing significant quantities of high explosive.

Gen. Said’s report covers up a multitude of mistakes under the guise of “confirmation bias.” In his report he notes that “[t]he overall threat to U.S. forces at [Kabul International Airport] at the time was very high,” with intelligence indicating that follow-on attacks were “imminent.” Perhaps most importantly, Gen. Said writes that “[t]hree days prior, such an attack resulted in the death of 13 service members and at least 170 Afghan civilians. The events that led to the strike and the assessments of this investigation should be considered with this context in mind.”

If that is indeed the standard, then Gen. Said must consider the words of President Biden at a press conference held on Aug. 26, after the ISIS-K attack on Kabul International Airport. “We will hunt you down and make you pay,” Biden said. “We will not forgive, we will not forget.”

Revenge was clearly a motive, with the drone operators leaning forward to put into action the President’s directive to hunt the enemy down and make them pay. Did the drone operators see children in the video feed? They say no, even though the C.I.A. analysts saw them prior to the launching of the Hellfire missile, and Gen. Said saw them after the fact.

These same drone operators were riding high on four years of “hands off” operations, where they were free to launch drone strikes under a “reasonable certainty” standard which was put in place knowing that the result would be more innocent civilians killed.

“Some of the Obama administration rules were getting in the way of good strikes,” one U.S. official is quoted saying about the need for looser restrictions. Gen. Said makes no reference to the impact the Trump-era policy had on conditioning drone operators to be more tolerant of civilian casualties, even to the extent that they looked the other way if acknowledgement of their presence could prevent a “good strike.”

What’s Wrong With the Program

The drone strike that killed Ahmadi and his family in many ways embodies all that was wrong with the U.S. lethal drone program as it was implemented in Afghanistan and elsewhere, failing to further legitimate U.S. national security objectives while harming U.S. credibility by wantonly killing innocent civilians.

A case can be made for criminal negligence on the part of all parties involved in the murder of Ahmadi and his family. But it is unlikely that any such charges will ever be put forward. The attack clearly violates international law, although the Biden administration will claim otherwise.

Gen. Said acknowledges so-called “confirmation bias” without getting to the bottom of what caused those involved in the drone strike to get it so wrong. Gen. Said alludes to systemic problems, such as the need to “enhance sharing of overall mission situational awareness during execution” and review “pre-strike procedures used to assess presence of civilians.”

But systemic (i.e., procedural) errors can only explain away so much. At some point the professionalism of the individuals involved must come under scrutiny, both in terms of their technical qualifications to carry out their respective assigned missions, as well as their moral character in willingly tolerating the deaths of innocent civilians in the name of mission accomplishment. Gen. Said leaves open the possibility that someone, somewhere, in the chain of command of these individuals can decide that the events of that day was a byproduct of “subpar performance” resulting in some form of “adverse action.”

That, however, is just another way of excusing murder, of tolerating a war crime committed in the name of the United States.

The day after Ahmadi and his family were murdered by U.S. forces, ISIS-K, operating from a safe house near to where the N.E.I. country director lived, used a modified white Toyota Corolla to launch rockets toward the U.S. positions in and around Kabul International Airport.

Fortunately, there were no causalities. But neither was the ISIS-K attack thwarted by a U.S. drone program that had been tipped off in advance about the nature and location of the attack. The ability to kill innocent civilians while failing to interdict genuine security threats is perhaps the most accurate epitaph one could ascribe to the U.S. lethal drone program in Afghanistan.

Scott Ritter is a former Marine Corps intelligence officer who served in the former Soviet Union implementing arms control treaties, in the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Storm, and in Iraq overseeing the disarmament of WMD.