by Madiha Tahrir, published in the Boston Review, September 10, 2021

I have been kind of hoping that Imran Khan might have stopped the disappearances and drone strikes on Pakhtuns in Pakistan. And it’s possible he has. I hope so. Meanwhile, Madiha paints a vivid picture of the suffering induced in Pakistan Tribal Regions and around the globe by the U.S. War of Terror. ~jb

In Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (2016), Viet Thanh Nguyen writes that U.S. films tend to substitute American pain for Vietnamese pain. “Americans love to imagine the war as a conflict not between Americans and Vietnamese,” observes Nguyen, “but between Americans fighting a war for their nation’s soul.” The last twenty years of the so-called War on Terror have stuck to this script. Consider the sheer number of articles, interviews, and think pieces on the anguish and trauma of the American soldier.

A thriving subset of this genre reports on the mental afflictions of the drone operator. These psychic lacerations, caused by having to watch the murderous effects of their own handiwork, have been elevated beyond a clinical condition into a philosophical anguish called “moral injury.” The term originated in 1994 with psychiatrist Jonathan Shay, who argued that a diagnosis of PTSD did not sufficiently capture the “soul wound” inflicted when one commits acts “that violate one’s own ethics, ideals, and attachments.” Following the start of the drone war, dozens of articles in outlets such as GQ (2013), Slate (2016), NPR (2017), the New York Times (2018), and the Washington Post (2021) followed—along with scholarly publications across the political spectrum—probing the mental states and suffering of the United States’ newest class of violence workers (a term I borrow from David Correia and Tyler Wall).

Lost in all this business of soul-wounded warriors is the relatively unfashionable wounding of empire’s targets. It doesn’t make for the kind of war story Americans want to learn about. A friend who is an award-winning magazine journalist explained the craft to me like this: “You have to ask yourself, if this story were a movie, what role is Matt Damon going to play?” The formulation is brutally honest about the seductive racial and colonial fantasies that are both subtext and, well, text of modern war reporting.

Where does that leave the rest of us—we, who belong to the browner parts of the Earth, we who are fighting on multiple fronts?

In Pakistan, the country of my birth, the country from which I became a refugee, the country to which I returned as a journalist and then as a scholar, I have had friends, comrades, and colleagues forcibly disappeared, sometimes killed. Particularly in the regions I have covered—the Tribal Areas along the border with Afghanistan that are being drone-bombed today and the province of Balochistan where a separatist movement is underway—the risk intensifies.

Photos circulate on Whatsapp groups—a confession, a beheading, a bomb blast, a body twisted and turned inside out. I once woke to photos of charred corpses, exposed bone and pink flesh, bloody as fresh butcher’s meat. It took me time to understand the diagram of these unholy bodies, where the legs should have been, where the mouth and the eyes must have once existed. The media relations arm of the Pakistani security forces had circulated the images as evidence of a “successful” counterattack against “militants.”

The United States began bombing the border zone, then known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), in 2004, ostensibly to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It has bombed the area at least 430 times, according to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalists, and killed anywhere between 2,515 to 4,026 people.

But the United States is not the only force bombing the region. Between 2008 to 2011 alone, the Pakistan Air Force carried out 5,500 bombing runs and dropped 10,600 bombs. The Pakistani security forces have also conducted scores of major military operations in the Tribal Areas as well as other Pashtun regions. There is no detailed accounting of the human costs of these military assaults.

When I traveled to the northern valley of Swat following Operation Rah-e-Rast (Righteous Path) in 2009, bullet marks and gaping holes scarred the low-lying homes along my drive. There, among others, I met Asfand Ali, whose brother and father were killed when a mortar shell blasted through their house. I asked him about the operation. “Whatever they do is just fine,” he told me. “They killed a lot of innocent people.” A ghost of a smile flickered across his face. “They can do whatever they want. It’s the government.”

Some time later, when I suggested to a Western leftist that we, we U.S. leftists, rework our analyses to account for the devastation caused by the Pakistani security forces, he disagreed. “What Pakistan does in Pakistan,” he shook his head, “that’s not our concern.” It was certainly my concern but, as someone with diasporic sensibilities, I have become used to pronouns like “we” and “our” as spaces of uneasy solidarities (to borrow a turn of phrase from Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang).

I also understand the impulse that drove his response. Global powers have repeatedly used the human rights abuses of other states, or the need to save brown women, or UN resolutions stating a “responsibility to protect” as pretext to invade less powerful nations. But, in restricting attention to the direct actions of the U.S. state, we fail to grasp the mechanics and manifold distributions of empire.

With the United States now shifting its strategy in Afghanistan from a direct military occupation with ground troops to an aerial drone bombardment conducted, it seems, in collaboration with the Afghan Taliban, it is critically urgent that we—we who dream of liberation—grapple with the complexity of imperial entanglements. What is happening with Afghanistan is less a withdrawal than a redistribution of imperial power. The United States is dispersing its war-making to collaborators and security assemblages that will help render empire difficult to track—a game that the United States has long played in Pakistan.

***

During my research on the war in FATA, I ran across a small handbill asking for help finding a missing teenager. The sheet had been distributed by his family. The boy had been badly injured when a U.S. drone bombed a funeral in the Tribal Areas. It was, in fact, the second bombing that day. Earlier, U.S. violence workers had killed several people in the same area; one of the dead, they thought, was important enough to draw out the senior leadership of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) to the dead man’s funeral, which happened later the same day. In their staunch belief that “terrorist” funerals only draw out other terrorists, they then bombed the mourners.

Here, I suppose I could pause and add an explanation of how we, we Muslims, bury our dead. This could include a description of the speed of funerals after a person’s death, or disclose funeral sociality in this part of the world. Certainly, a journalist reporting on the bombing for a Western press outlet felt compelled to clarify in an article I read that the attendance at funerals of Taliban figures was not limited to guerrilla fighters.

I hung at this sentence when I read it because I have written sentences just like it as a former journalist. You are trying to explain how it came to pass that dozens of people died, or you slip it in because you’re trying in your small brown way in a white media establishment to remind U.S. readers about the inordinate toll, or your editor asks for “context,” and you’re reduced to explaining the self-evident (funerals draw together family and community!) as if it were some peculiar borderland ritual.

I could also parse the statistics of this bombing—but I think that would all miss the point, which is that they bombed because they could.

Consider that drones are actually technological failures as weapons of war, if by “war” we mean a contested battleground. They are easily shot down and, as U.S. military officials have stated, they are unfit for fighting with a “near peer adversary.” This is why the U.S. Air Force is trying to retire the MQ-9 Reaper drone.

It follows, then, that to fly drones over the Tribal Areas requires not only coordination with Pakistani authorities for airspace, but also a whole host of largely opaque negotiations and arrangements that barter the lives of ethnic Pashtuns in FATA in the imperial war market. In other words, the “organized abandonment” (to use abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s terms) of border zone populations has been crucial to maintaining drone bombardment.

Checkposts and moveable checkpoints surveil, intimidate, and interrupt the movement of people, journalists, and information in and out of the Tribal Areas. These physical blockades have been augmented by a digital enclosure, especially in Waziristan, on the southern tip of the Tribal Areas, where bombardments have been heaviest. The strategic absence of sufficient electronic infrastructure—from the Internet to cell phone towers—has not only made the relay of information difficult following bombardments, but has limited the global circulation of photos and videos documenting the aftermath. In the Obama years, therefore, news stories on drone bombardment quickly took on a standardized, anesthetized structure: an anemic lede stating where the attack had taken place, followed by a quote from anonymous Pakistani officials categorizing the dead as “militants” or “civilians,” then a short final paragraph on the alleged lawlessness of the region. It became small news.

British colonial knowledge, predating Pakistan’s independence, still underwrites these arrangements. Gazettes, tribal descriptions, and genealogies produced by colonial authorities remain standard fare on the bookshelves of Pakistani bureaucrats and analysts. The largest bookstore in Islamabad, which caters to the instrumental knowledge class—including Western ambassadors, the CIA, the U.S. State Department, and other administrators, UN officials, and NGO workers—keeps these colonial texts in stock for its customers, alongside more recent pop literature by U.S. terrorism experts.

After independence, this knowledge shaped the continuation of a colonial regime in all but name within the Tribal Areas. There, the Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR), a draconian set of laws enacted by the British and justified as granting tribal autonomy, continued to be enforced. Under these regulations, FATA Pashtuns could not vote. Instead, an appointed Political Agent with sweeping powers governed each of the administrative districts or “agencies” that make up the Tribal Areas. The agent was judge, jury, and administrator. He could deliver executive judgments and detain entire communities on suspicion of a crime by one of their members. While the FCR was formally repealed in 2019, meaningful change has yet to take shape on the ground.

The War on Terror, particularly as manifest in the Tribal Areas, remixes the colonial-era stereotype that Pashtuns are especially fanatical with post-9/11 fears about Pashtuns’ alleged propensity for terrorism. Not only does the propaganda arm of the Pakistani security forces churn out films that regularly depict Pashtuns as terrorist villains, but private television shows and advertisements also ridicule Pashtuns as extremists.

Poorer Pashtuns, especially, have been subject nationwide to police crackdowns, raids, and the razing of katchi abadis (squatter settlements). Following a bomb blast in Lahore, for instance, a traders’ association demanded identity documents from Pashtun traders, and the police circulated notices about surveilling Pashtuns as well as Afghan refugees, some of whom are ethnically Pashtun. (Sanaa Alimia has richly documented how identity documents work as a means to surveil and control these Afghan refugee communities.)

In short, while there are caricatures about all ethnicities in Pakistan, only one of them is conflated with the Western fantasy of the “terrorist.” Pashtuns have become what Samar Al-Bulushi calls “citizen-suspects”—racialized populations subjected to suspicion, surveillance, and paranoid state imaginaries, thus making them vulnerable to overwhelming state violence. Pervez Musharraf, the military dictator who seized power in a 1999 coup and collaborated with the United States following 9/11, was explicit about his government’s strategic abandonment of Pashtuns specifically and Pakistanis more broadly. Asked by the CIA how the agency could conduct drone bombings without admitting responsibility, Musharraf was dismissive. “In Pakistan,” he said, “things fall out of the sky all the time.”

This is how the funeral came to be bombed. But these genealogies of violence do not make for good copy, so we—we who know better—settle for a docile sentence about how villagers attend funerals too.

Luckily the boy was still alive, but in urgent need of medical attention. He was badly burned and bleeding. The local hospital could not care for his wounds. So, his father and other family members loaded him into an ambulance, and it sped off toward the nearest well-equipped hospital several hours away.

***

In 2006 two journalists appeared before a Pakistani court as defendants. They were accused of leaking official secrets because they had been filming at Shahbaz airbase, a Pakistan Air Force holding, in the southern city of Jacobabad. The base was one of the earliest used by U.S. forces for flying drones in the region.

While the use of the airbase may have technically been secret, it was of course known to Jacobabad locals; no fewer than three Predator drones had crashed in and around the city in 2003 due to technical failure. In addition to drones falling from the sky, the increased securitization of the area had alerted uneasy residents to the goings-on at the airbase.

This may have been why television reporter Mukesh Rupeta and cameraman Sanjev Kumar were filming at the airbase when they were picked up and disappeared. Unlike ordinary arrests with their attendant paperwork and bureaucratic procedures, disappearance makes it difficult to know who or which agency has taken someone, where the detainee has been taken, and whether they will ever be seen again—and that unknowability is the point. Without accountability, the state’s agents are able to engender spaces where things can fall out of the sky, where the potential for violence is enormous.

In this case, Rupeta and Kumar were turned over to the police three months later. While police officials refused to say who had initially detained them, a relative of one of the men told reporters that they had been detained by Pakistani intelligence officials linked to the military, and that at least one of the reporters had been tortured.

A week before Rupeta and Kumar were presented in court, the body of another journalist was found dumped in Miranshah, the capital of North Waziristan in FATA. Hayatullah Khan was a Waziri reporter who, six months earlier, had photographed remnants of a Hellfire missile, the first visual proof that the United States was bombing the border zone. The photos were published in international news outlets, and the next day Hayatullah was disappeared.

On the U.S. news, I often heard experts and analysts claim that part of the appeal of drone warfare to the Obama administration was that it offered a viable alternative to detentions. John Bellinger, the former legal advisor for the Bush administration, told audiences in 2013, “This government has decided that instead of detaining members of al-Qaeda [at Guantánamo] they are going to kill them.”

But all the while in Pakistan, secret detention centers and black sites continued to metastasize. Together they constitute Pakistan’s “little Guantánamo Bay,” as rights activist Amina Masood Janjua puts it. During the early years of the war, Musharraf literally sold detainees picked up in Pakistan to the United States. We know this because the ignominious buffoon boasted about it in the English edition of his autobiography. He admitted to auctioning 369 detainees; the figure that Pakistan handed over may be as high as 800. While some of these people ended up in Guantánamo, others were disappeared into CIA secret prisons in multiple countries.

In Pakistan, U.S. operatives, working jointly with their Pakistani counterparts, interrogated prisoners in secret locations. Pakistani security officials also acted as the heavy in many cases, detaining and torturing prisoners. Moazzam Begg, perhaps one of the most famous detainees, was initially held by the Pakistani spy agency, the ISI, at a house used as a detention site in the G-10 neighborhood of Islamabad. The CIA’s prison program was eventually terminated but, by then, detention was beginning to take on a life of its own inside Pakistan.

In 2011 the Pakistani government used anti-terrorism as a justification to formalize roughly forty internment centers. While little is known about these sites, almost all of them appear to be based inside existing prisons, military forts, and jails. All of them are also located in the predominantly Pashtun regions of the country, which underscores the racialization of Pashtuns as terrorists.

These practices have been especially difficult to track in FATA in part because arbitrary detention and collective punishment—often described in other contexts as “extrajudicial”—have been, in these regions, legal. Under the FCR, that legal remnant of British colonial rule, people could be detained for up to two years at the will of the Political Agent with no recourse to courts. Add to the blockades, military forts, internment centers, and jails of the Tribal Areas the carceral spaces across the rest of the country—more internment centers, military and paramilitary bases, secret compounds, and ordinary jails where the disappeared sometimes mysteriously reappear—and an entire carceral geography flickers into view.

Documenting these practices and carceral spaces, however, can land one in trouble. Activist Alamzaib Mehsud, who is attempting to keep an archive of detentions, disappearances, mine blasts, and extrajudicial murders in FATA, was himself picked up in January 2019 and charged with rioting and inciting hatred for an allegedly anti-military speech. He was released almost nine months later.

The War on Terror is not the first time the Pakistani government has deployed detention and disappearance. During the 1973 insurgency in Balochistan, Pakistani forces disappeared Baloch activists, and under the U.S.-backed regime of military general Zia ul-Haq in the 1980s, critics and dissidents were, at times, picked up and disappeared.

With the War on Terror, however, these practices have expanded in both scope and geography. A wider array of dissidents, activists, and critics has been detained, as well as a host of other individuals deemed by the state, because of ethnicity or class, to be suspect: madrassa students, laborers, bus passengers. Sometimes the disappeared return in strange form. In March this year, road workers at a construction site in the Tribal Areas unearthed the bones and personal effects of a teacher disappeared thirteen years ago.

In an act that would be parodic were the stakes not so horrific, the Pakistani government has set up a Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances: the government looking into government crimes. It is a largely toothless affair, for the committee dares not name the military perpetrators. Police reports of disappearances, when the family manages to get them filed, regularly note down that the suspected perpetrators are na maloom afraad, unknown persons. It works as a shorthand: we, we Pakistanis, know who the Unknown are.

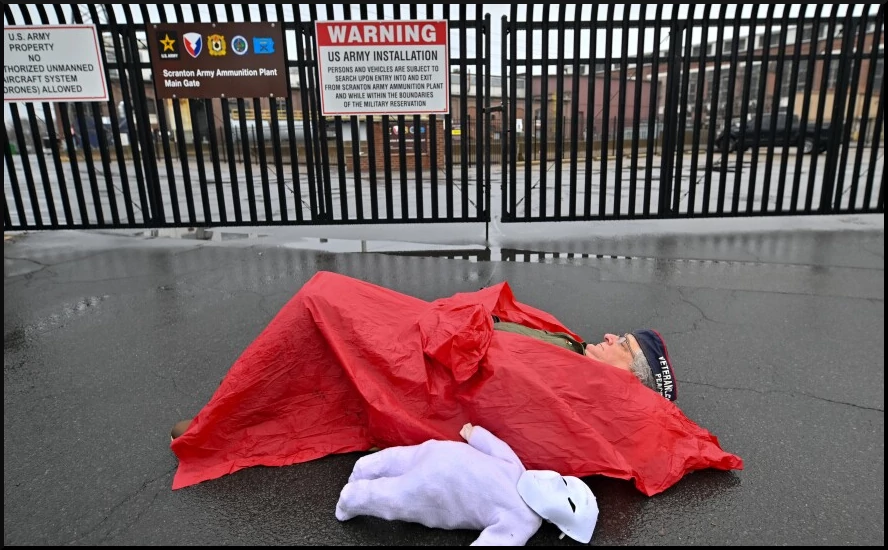

These carceral geographies are also available to bolster U.S. empire and drone warfare. Karim Khan, an anti-drone activist, was disappeared in 2014 days before he was due to speak with European parliamentarians and the International Criminal Court at the Hague about drone bombardment in the Tribal Areas. (U.S. violence workers had killed Khan’s son and brother when they bombed his home in 2009.) Khan’s captors did not identify themselves, but the method of his disappearance—plainclothes men accompanied by police officers who bundled him into an unmarked vehicle—bears the hallmark of the Pakistani security apparatus. During his detention, his captors beat him and interrogated him about his contacts, other drone victims, his upcoming trip, and what he intended to make public. Karim was released after nine days and, though he still traveled to Europe to testify, the detention scarred him. When I saw him after, he appeared withered and reported difficulty sleeping as well as bouts of anxiety. Alamzaib, too, was picked up again in 2020 from his home hours after posting a video on social media criticizing U.S. drone bombardment and asking questions about the Pakistani military’s complicity. He was not disappeared. In his case, the local police served as captors, taking him without an arrest warrant and keeping him for twenty-three days.

And so, this is what I know about what happened to the boy on the missing poster, the one who had just barely survived the US bombing of the funeral. As the ambulance sped toward the hospital, Pakistani security forces blockaded the road and stopped it from passing. They ordered everyone out of the vehicle. The ambulance driver, the boy’s father, the relatives traveling with him—and the boy himself—were all disappeared.

***

Is this a story of U.S. empire or of Pakistani state impunity? And what are the stakes when drawing such a distinction?

The story about the boy’s disappearance doesn’t fit neatly into the popular understanding of what drone warfare looks like. Our conceptual frames tend to restrict our attention to the deaths and injuries caused instantly by Hellfire bomb blasts, but the lives of drone survivors, and of the communities living through the war, go on. Drone survivors, like others in the border zone, are also people who have cousins taken by the Taliban, or an uncle whose decomposing body is found in the market after several months of disappearance, or a brother who is detained indefinitely by the Pakistani military.

The failure to see the full scope of the war has the effect of isolating the drone from the broader social and material worlds that make the drone war possible. This blindness rehearses the logic of U.S. empire. Preferring to frame its interventions as temporary and limited, the United States has been adept at distributing its capacities for violence among networks of collaborators. It need not explicitly demand the detentions of Rupeta, Kumar, Hayatullah, Karim, or Alamzaib. Having set the broad terms of its imperial project through opaque arrangements with the cruelest segments of the Pakistani state, it can disperse its war-making among transnational security assemblages.

For the Pakistani security state, in turn, the U.S.-led vitalization of terrorism as an ideological framework has enlarged the space for its own geopolitics, sometimes in tension with the United States but always in loose collaboration. These take many forms, including attacking critics in the name of national security, using War on Terror rhetoric to assault peasant movements and thieve land, passing broad surveillance and anti-terrorism laws, committing extrajudicial murders and totalizing military operations, forcing mass displacements that have reshaped FATA, and using the war to intervene in Afghanistan.

For the United States, the expansion of these Pakistani militarist projects has allowed for a displacement of responsibility, and the ability to strategically shift scales. Western and international publics may be attuned to direct U.S. actions, but “local” cases of detention, disappearance, extrajudicial murder, and even military operations go largely unnoticed. This is the distributed empire of the United States, one that exceeds the direct actions of the U.S. state—and continues to shape lives long after the drones have gone.

It has been years now since the boy was disappeared. Everyone else has been released, but he remains an absent presence. Sometimes, people never return. But, when I speak to a member of his family, I cannot ask that question, so I ask instead, “How is the family nowadays?”

He understands, responds, “We are searching for him.”

Madiha Tahrir is a Pakistani American journalist and researcher.